It’s interesting to me how often the words strategic thinking and creative thinking together are used in business conversations. More concerning, I’m not 100% certain we always know what these words mean.

This is particularly complex in classes and workshops where I try to explain them – or more annoying, when I try to explain the differences between them.

At the same time, other themes pop up – like insights, convergent thinking, innovation, critical thinking, design thinking.

Everything gets muddled, and I end up in a classroom with a lot of students more confused than ever.

First, Let's Admit It's a Complicated Conversation

Someone at work tells you to go be strategic. What do they mean exactly?

Maybe someone asks you to be creative. Again, what are they asking you to do – precisely?

Here’s where the problem starts.

If you and this other person (like your boss or supervisor) don’t agree from the start on what you’re being told to do, what are the chances you’ll do what they want successfully? This disconnect applies even more specifically to senior people who give instructions to team members, and their staff doesn’t do what they want.

That just means more re-work for everyone!

If we want people to be strong problem solvers – which means using both their skills in strategic thinking and creative thinking – we need to have some simple agreement at the beginning about …

What are the different ways of thinking, what’s the purpose, what to do

What the differences are between them, so they don’t do one thing when they should be doing the other, and

How are they inter-related, so both can be used most efficiently and effectively.

Otherwise, people tend to do what they think is right, hope it’s correct, then find out later it wasn’t right (or they did it right by accident or luck), but in the end …

What did anyone learn?

And, most of all, how will they (or you) get better next time?

Let me explain this visually

To try and help people understand all of these important terms, I use a simple(-ish) diagram I’ve named The Hourglass Figure to put all of the individual pieces of strategic and creative thinking together.

Before I get started, let me also admit two terms do not neatly fit in this diagram: analytical thinking vs critical thinking.

Because they deserve their own discussion, so it’s in a separate post here.

Ready? Let me explain all of this stuff with some shapes and some colours.

Welcome to the Hourglass Figure

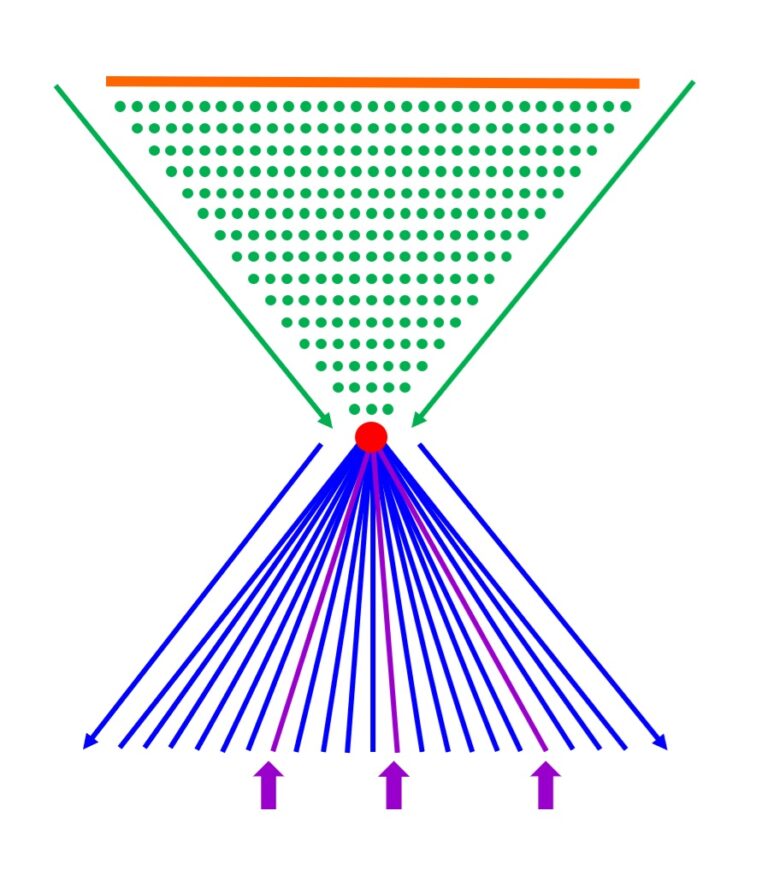

Please indulge my crude drawing to the right. (Believe it or not, I have a design degree!)

To start …

Think of any time at work when you were given a new project or assignment to manage.

After the supervisor placed the Tiara of Responsibility on your head, they sped off in the other direction with a puff of smoke on their heels. You were left behind without any direction, detail or suggestions.

In other words, you had to decide for yourself what to do to get started.

The Hourglass Figure shows you what you (probably) did. Or, more precisely …

Here’s what you should do in the future to use both your strategic thinking and creative thinking together.

1. Always start with your goal or purpose.

ALWAYS ALWAYS ALWAYS start any project or assignment with a goal or purpose. What are you trying to do, and why?

George Doran taught us to be. Not always easy, but if my experience is any indication, the one letter of SMART you cannot ignore is ‘T’.

If you don’t at least put a time-frame on when you have to accomplish your goal, when will you or your team members do it?

(Answer: Whenever they want.)

If you aren’t sure it’s the right goal, ask a constructive person in your team to help, if not your boss or supervisor so everyone agrees from the beginning.

So, the thick orange line at the top of the figure represents your goal(s).

Not to be pedantic (ok, yes I am), remember your goal is not your outcome.

A goal is what you want. An outcome is what you get. They are not the same thing.

Next up, you need to …

2. Gather information.

In some organisations, it’s more specifically called conduct research.

The information you gather will come from one of two general places: inside the organisation, and outside the organisation.

Internal sources might be gathering and reading existing documents, talking to employees (team members, yours or others; frontline sales people or those who talk directly to end users; staff in other departments, such as H.R., procurement or legal), or reviewing in-house procedures or protocols. (‘how we do things around here.’)

External sources might be talking to clients, constituents or other types of end users; searching the Internet; making a site visit to talk to people in a factory, sales floor or traditional media.

Aside #1 It’s important to research internally and externally. If you only use one type but not the other, it could lead to bias, if not biased decisions. It also gives you something very powerful: a bigger perspective than your own.

So, let’s imagine that each piece of information you gather is represented as a green dot in the top row underneath the orange line.

Here’s where things get interesting.

Is your research any good?

As you examine all this stuff, you may realise you have way too much. It’s a mess. It contradicts. It repeats. Or you don’t know where to start because you went out to the pub last night and this morning it’s hard to think. (Go ahead, admit it.)

This is a common affliction known as analysis paralysis. (Not the pub part, that’s a different type of paralysis.)

The only way out is to analyse what you have. (Hello Analytical Thinking!)

Aside #2 The process you’ll be going through is called DIKW or, in a bit more depth, The Information Chain. You move through data to information to knowledge to wisdom or insight to ideas. If you want more, here’s .)

Aside #3 As you examine your research, you’ll begin using your .

In short, Analytical Thinking is looking intently at one thing. Critical Thinking is comparing that thing to something else to understand it better.

For each piece you gathered …

You need to analyse it to decide its value.

- Some of the information will be good. It helps guide you toward a decision, insight or potential idea.

- Some of the information will not be helpful as you originally thought. But, it may lead you to research other areas – which can be equally helpful.

- Some of the information will be not useful at all. In fact, when you compare and contrast information (hello Critical Thinking!), you may realise some pieces of data are …

- Not useful in this specific situation

- Not useful at all – in fact, it’s factually wrong, or

- You’ve made an assumption without any proof or reasonable evidence

Aside #4 When your brain doesn’t have a piece of information, it – that is, you – makes up information to fill the space. This is an assumption. To paraphrase the familiar statement: Do not believe everything you think unless you have actual facts – not alternative facts.

Aside #5 Also, remember this vital piece of advice from Walter Shewhart. Information without context is useless.

Ok, It’s Time To Get Rid of What Isn’t Helping

As you critique your information, get rid of what does not help you. Reduce. You want less – but better quality – information.

Think of it like boiling down chicken broth into consommé. You start with a lot of broth, but as you reduce it, the liquid becomes more concentrated and more flavourful.

To return to the diagram, you have less – but better – green dots as they move down toward the red circle in the middle of the diagram.

Now you’re getting to the most powerful part of your thinking, and also where you begin to switch how you think.

3. Determine what insights you learnt from your research.

At this point, your thinking must move toward a conclusion, one of any of these three options: an insight, a decision, or a single idea.

Aside #6 Be careful of coming up with only one idea. Sometimes the situation is so simple you don’t need to overthink. But, you also don’t know if a single idea is good because you don’t have anything to compare it. At least come up with a Plan B so you know your first choice is actually the best choice.

Sorry, back to the point. As it related to all this information …

What do all these green dots mean, or

What does this new learning suggest we do – or not do?

The green dots lead to the red circle, which is the key turning point between the upper and lower halves of the diagram. You are transitioning from:

Drawing conclusions from your research (What is your wisdom or insight? What did you learn?) to

Deciding how to put the insights into action.

From here, now your thinking takes a new direction. You go from converging your thoughts to diverging your thoughts.

4. Turn your insights into action.

About your project or assignment, it’s time for action. But what action? Time to do a different type of thinking: not contracting, but expanding.

Each potential step or action is represented by a blue line radiating from the red circle.

Good insights should inspire many actions, so much so that you should have many blue lines. You want more options than less.

Similar to the upper half of the diagram (the green dots) where not every piece of research is relevant, not every potential action step (the blue lines) is relevant either.

In fact, it’s probable up to 90% of your potential actions are useless, illegal, stupid, been-there-done-that, immoral, too complex, etc.

But – and this is the essential part – the remaining 10% is where should focus because here is your value.

Aside #7 If you’ve never heard of , you need to. It governs every brainstorm, and you can’t change it.

As this step concludes, you want the gist of a plan of action. (Not the plan, just the first draft of plan.)

5. Select, refine and improve your best ideas.

Even narrowing your potential steps down to the best 10% is still a lot. It’s time to refine, improve and put your best options into action.

Similar to Shewhart’s claim about information and context, creativity without action is useless. To have a great idea but not implement it is as poor as having a bad idea.

So, the purple arrows at the bottom of the diagram represent your very best solutions – refined, considered, sourced, operationalised and priced – ready to be implemented.

And hopefully, by implementing your best action, you will achieve your business goal and reach the desired outcome.

I wish this diagram had one more element. There should be a line connecting the bottom of the diagram with the top.

From thinking of my own experiences and talking to others, I’ve known many situations where the entire process went so far askew none of the business goal wasn’t achieved.

Before you launch your plan, give one more moment’s thought to ask yourself whether your action plan will achieve your goals.

And there you have the Hourglass Figure, shown below with all the key details and definitions.

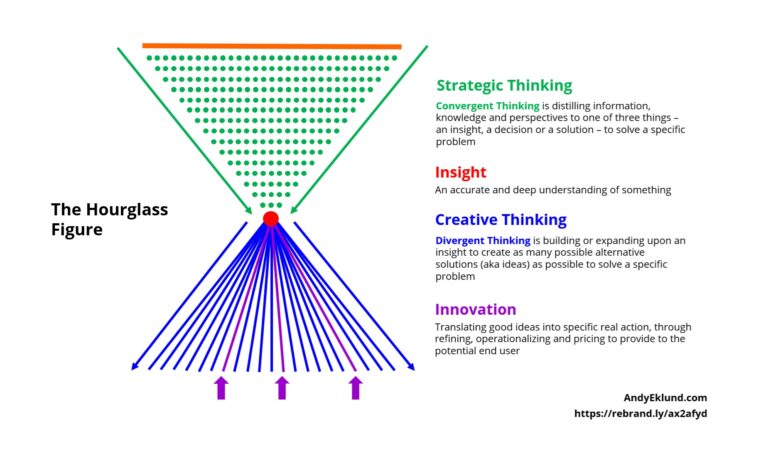

Strategic Thinking to Insights to Creative Thinking to Innovation

With the Hourglass Figure fully drawn, here are the key themes and terms put in order.

The top of the hourglass (the inverted pyramid) is Strategic Thinking which has many parallels to Convergent Thinking – distilling information, knowledge and perspectives to one of three conclusions (an insight, a decision, or a single solution) to solve a specific problem.

The distillation of strategic thinking to an Insight, or more generally as wisdom, is the red dot.

It is the turning point between strategic thinking and creative thinking.

The bottom of the hourglass (the upright pyramid) is Creative Thinking with parallels to Divergent Thinking – where one’s imagination takes the insight and brainstorms as many possible alternative solutions as possible to solve a specific problem.

Finally, when the best ideas are chosen, they are refined, improved and operationalised to become action.

If creative thinking is actively thinking up new ideas, then innovation is actually doing something. (I’m paraphrasing Theodore Leavitt, former professor at the Harvard Business School.)

Notice too that strategic thinking and creative thinking are opposite and complementary. Neither way of thinking is right nor wrong. They’re simply different ways of thinking. Each has a separate and vital purpose.

In the end, you can’t be an effective thinker if you don’t use both strategic and creative thinking in a compatible way.

Finally, depending upon which business psychologist you trust, aren’t these two ways the majority of your thinking every day at work?

Does All This Work So Neatly?

No, never.

Sometimes I’ve had to go back and re-think the goals. Or, I’ve had to go back and conduct better research. Or my insights were really assumptions. Or, I didn’t have enough ideas. Or I couldn’t articulate an idea to the point to make it actionable. Or I couldn’t sell it my idea/proposal to a senior leader. Or my budget was cut. Or my boss left the company. Or I moved to a different position. Or I just got burnt out and found a new job.

In other words, you jump between the green-style thinking and the blue-style thinking, and vice versa and back again. Sometimes you think you have the red dot, or the right purple arrow, and then something goes awry.

Or, in plain old English …

You keep learning

You remind yourself of what you’ve learnt (so you don’t do it again)

You have a laugh at yourself

You adjust your belt or your lipstick, or both

And you keep going.

Like life itself, business wishes it was linear, but it isn’t.

But, if you know at least where you’re going and why, it’ll be a lot more entertaining ride.

Now that you have the full perspective, you want to look now at Analytical Thinking vs Critical Thinking to compare it with the Hourglass Figure.

Do you have other ways to define Strategic and Creative Thinking? Please post your thoughts and comments below.

No comment yet, add your voice below!