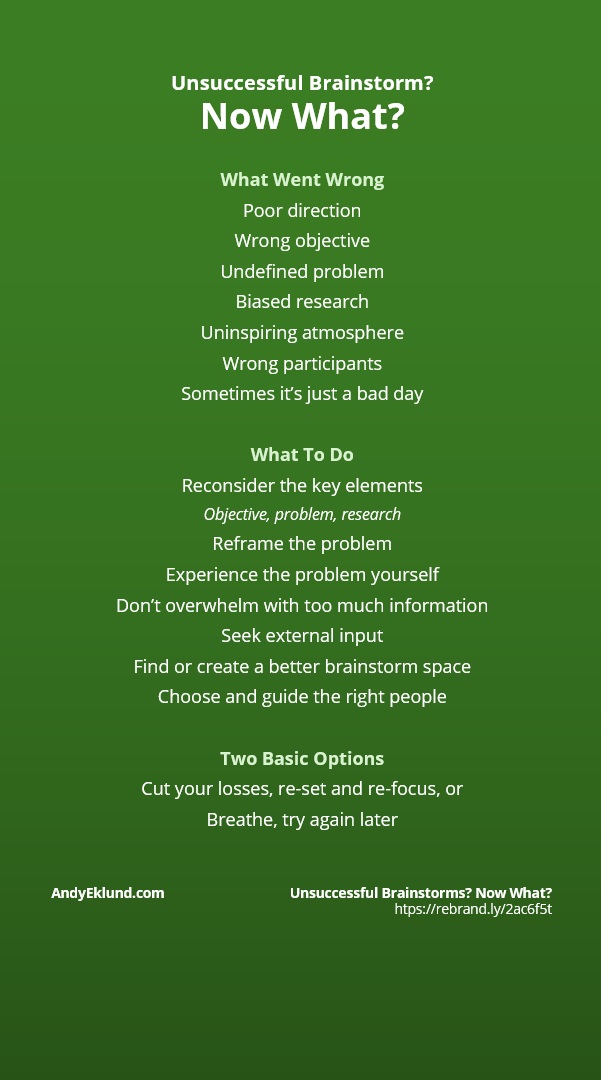

It’s going to happen, if you haven’t experienced it already: an unsuccessful brainstorm that didn’t generate one single usable idea.

This topic came up yesterday when I was talking with a friend, who’s also a brainstorm facilitator. We both rely heavily on relentless optimism (aka positive thinking) in that we know in our hearts we’ll eventually find the best idea.

(Don’t take my word for it. Research has shown that relentless optimism can have a profound effect, not just on brainstorming, but life in general.)

Nevertheless, unsuccessful brainstorms occur. So what to do?

Ironically, use a bit of creative problem solving to identify the issue and eliminate it.

There might be something wrong with ...

The objective or purpose

The single reason for most unsuccessful brainstorms is that there wasn’t a clear purpose or direction from the start. Why have a meeting when a simple conversation between two people would be better. What do you want the idea to do? How will you select the best idea, and what criteria will you use?

Possible solutions? The brainstorm sponsor and the facilitator should meet in advance to determine the basic foundations of WHY a brainstorm is the best situation. Consider a creative brief so all of the key pieces of information are gathered. Don’t use the same objective again and again. Trying re-framing the problem so you have a different direction to start. Start the brainstorm with the objective so participants also know the purpose, if not discuss the objective with participants in advance of the meeting to increase sub-conscious thinking.

The problem itself

Brainstorms are as much about creating ideas as they are about managing the problem. In other words, you need to start any brainstorm, whether formal (a by-invite meeting in a conference room) or informal (a table in the canteen) with the specific problem for participants to solve. That begs the question: are you solving the right problem? Are you solving the symptom or the actual problem?

Or, is it clear what the idea is meant to do with the problem? Ideas only do to three things. 1) Eliminate the problem. 2) Minimise the problem. 3) Contextualise the problem. Not only are they three different directions, the strategy itself means different ideas or solutions..

Who defined the problem? It shouldn’t be you per se, unless you are experiencing the problem directly. In most situations, business is trying to understand the problem from the point of view of the consumer, customer, end user, voter, etc. If you only understand the problem from your point of view, you don’t understand the problem.

If you can’t get to the end user directly, seek input directly from someone who is knowledgable, who has background or history with the audience or problem, or who has an objectivity or balance to help you take a step back from the issue to understand what may be the underlying problem to address or understand.

Possible solutions? Ensure you have agreement on the problem internally, either with management or trusted colleagues. Determine what the idea should do, again with internal discussion or feedback from the end user. Gather relevant information about the target audience you want to influence. Focus more on psychographics than demographics..

That said, don’t overwhelm the participants with so much information it’s hard to extract themselves from the data. Try squinting, which is an IDEO technique to “squint” at something to focus on the big things and less on the details. What are the key things the participants to know about the goal, problem or audience?

The research

A typical example of ‘wrong research’ is that it’s not accurate to the target audience. It’s either too superficial, or too oriented to demographics and not psychographics. Is the research biased? A common misconception with conducting research is that you should try equally to prove yourself wrong as you try to prove yourself right.

Possible solutions? As much as possible, start with primary research – which means, in plain English, talk to the person directly. Whether it’s the customer, a member of senior management, a policy director, whomever, primary research means you’ll have immediate access to the person with the information you want. It’ll likely be the least biased if you listen to understand and not listen to reply. When you treat them respectfully, make them feel comfortable (no agendas, like trying to sell them seomthing on the side), and truly listen to what they’re trying to tell you, they’ll tell you honestly and transparently what they think, believe or want.

The environment

Often, the physical space isn’t conducive to brainstorming. Distractions. Too formal. Uncomfortable. Resource-less (no stimulus to generate ideas, not even any food or drink).

Possible solutions? Go some place else, or if at all possible, go outside where the environment doesn’t create stress. Bring more and better stimuli into the brainstorm. (Even a cast-away magazine with visuals is better than nothing!) Food and beverage never goes astray.

The participants

Perhaps the most common, and most difficult to work around. A single person detracts and distracts the collective imagination. They’re negative, or positive but domineering, or stuck on assumptions, or unable to express themselves. (Maybe that’s even you?)

Posible solutions? First and foremost, talk to the right people. Idea people. People who understand the problem or target audience.

Of course, it’s not always easy to get rid of or avoid the negative people. Isolate the problem. Is it their history with the problem that’s clouding their judgement? (The more you know about something, the less creative you are, full-stop truth.) Are they distracted? Do they have another opinion that needs to be acknowledged, not necessarily agreed-to? If they’re too important and you can’t work around them, have a separate brainstorm where they aren’t involved.

If the problem is you, get someone else to guide the thinking, if not take the brainstorming out of your hands. The only thing you’ll need to provide are good relevant critieria so the other party knows what to look for. You don’t have to lead every project; having good people around you to step up not only shows you’re willing to be flexible, but you’re also a good leader.

What if it’s the whole group, not just a single participant? Perhaps the team needs to be re-organised. Perhaps there’s something political going on? Instead of one large group, schedule two smaller groups, or talk to be individually. And last – and I say this with a great deal of respect – but again, is the problem you?

It may not be something you can identify.

After you’ve looked at all the circumstances, and still can’t understand the problem, it’s time to cut the losses and start again in two ways.

- You can take the hard and drastic path. Fire the facilitator and get a new one. Get a new set of people. Ask yourself if YOU are the problem.

- You can take the simple and fresh path. Stop and breath. Let unconscious/passive creativity work on the problem while you and your team go on to something more pressing. Get a facilitator to help you manage the process. (Are you doing too much?) And most of all, remember you have relentless optimism.

It’s very likely the idea is there, it’s just not ready to show itself, so start again tomorrow after a good night’s sleep.

Here’s a similar article you may find useful: Six Problems with Brainstorming and How to Overcome Them.

How else have you dealt with unsuccessful brainstorms? Please add your thoughts and comments below.

No comment yet, add your voice below!