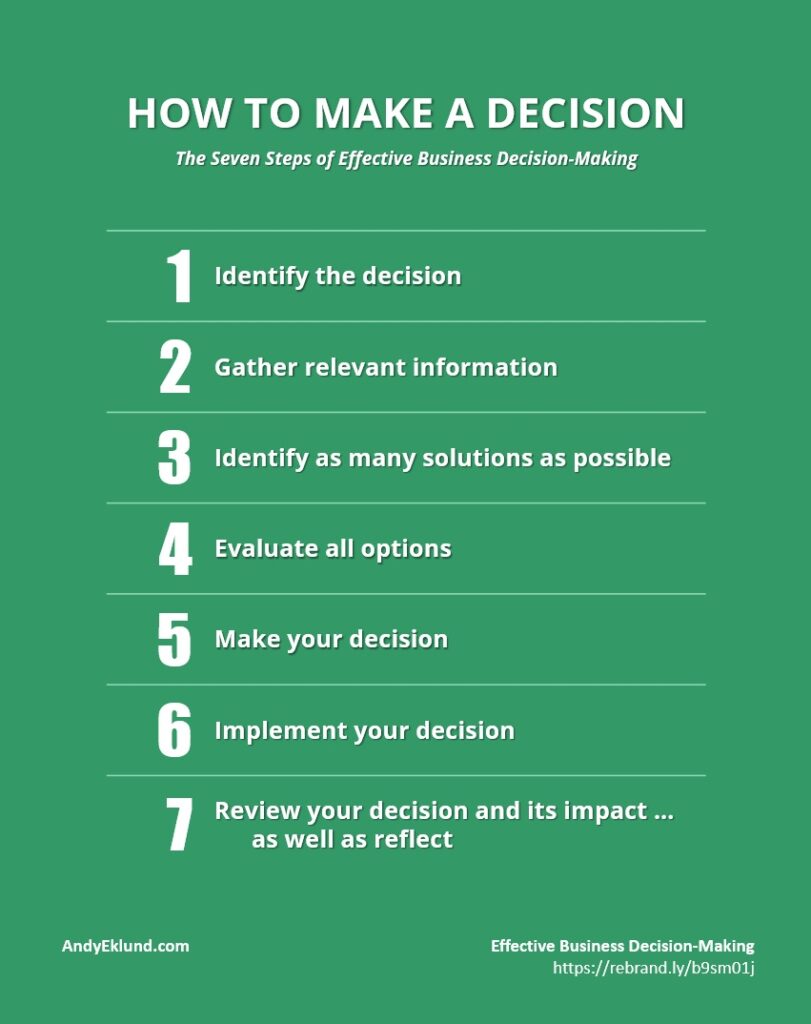

Effective business decision-making involves a seven-step process that’s been defined and refined pretty much since modern business began with the Industrial Revolution in the late 1800s.

While the process is relatively simple across seven broad areas, it’s also a step-by-step guide which can be endlessly adapted.

Expand it as needed for complex and challenging decisions involving an entire organisation, or scale it down to the simple but necessary steps to make the ‘regular’ decisions we make every day.

The Seven Steps

Click on any of the subheads below to jump to that step. Use the blue arrow in the bottom right of your screen to return to the top of the page.

This first step sounds simple, but it’s key.

To be an effective decision-maker in business, you must realise you need to make a decision.

To solve a problem, you must define the decision you need to make – or the outcome, or both – as specifically as possible.

You may also need to consider these adjacent questions:

What is the specific problem that you need to solved? You cannot adequately solve vague problems.

Is this the real problem – or is it a symptom? In other words, make sure you’re solving the right problem.

Truthfully, can you solve this problem? Some problems may be wicked problems, and if so, will take considerable resources to solve.

What general action will you need to take to solve the problem? You only address problems in three ways: eliminate the problem, minimise the problem, or put the problem into context.

What is the goal you hope to achieve by implementing this decision? SMART Goals are one way to do this.

How will you measure your goal or decision?

Alternatively, are you trying to jump on an opportunity or trend? They’re enticing, and often have immense potential. But, at the same time, be careful. Opportunities and trends can be fickle. How do you know they’ll continue to be opportunities or trends later on, or will you just be a ‘me too’?

The key – especially if you love chasing opportunities – is to focus. Don’t chase everything. It’s better to try answering two key questions:

- Is the cost of entry worth the potential distraction from the existing business?

- Conversely, will the existing business suffer due to splitting focus?

Finally, realise there’s something out there called decision fatigue. It’s a smudgy virus, but it usually involves making poor decisions when you have too many decisions to make. (For example, you speed through making decisions without truly thinking about the true impact.)

If nothing else, you might remember the acronym HALT when you need to make a decision.

Step 2: Gather relevant information.

A different way to describe this step is to do research. You are essentially building your case for understanding the decision, the outcome, the problem and the potential action steps. By gathering information – figures, data, statistics, testimonials, best practices, customer feedback – you can make informed, productive decisions and not just knee-jerk, impulsive choices.

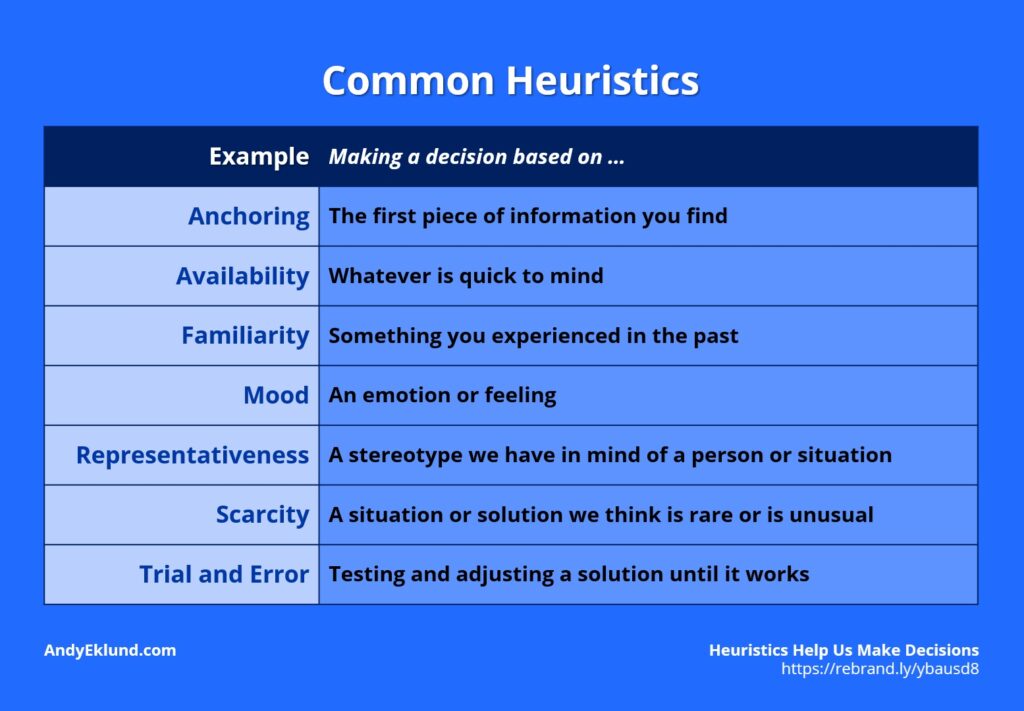

To make a decision, you don’t want to rely upon simple heuristics to speed up your decision making.

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that allow people to solve problems and make judgments quickly and efficiently. In the link above, see seven of the most common types of Heuristics. (Click here for my article with more information and examples of what each type means, or click here for an article from Verywell Mind, an excellent website to find information about mental health.)

Information Bias!

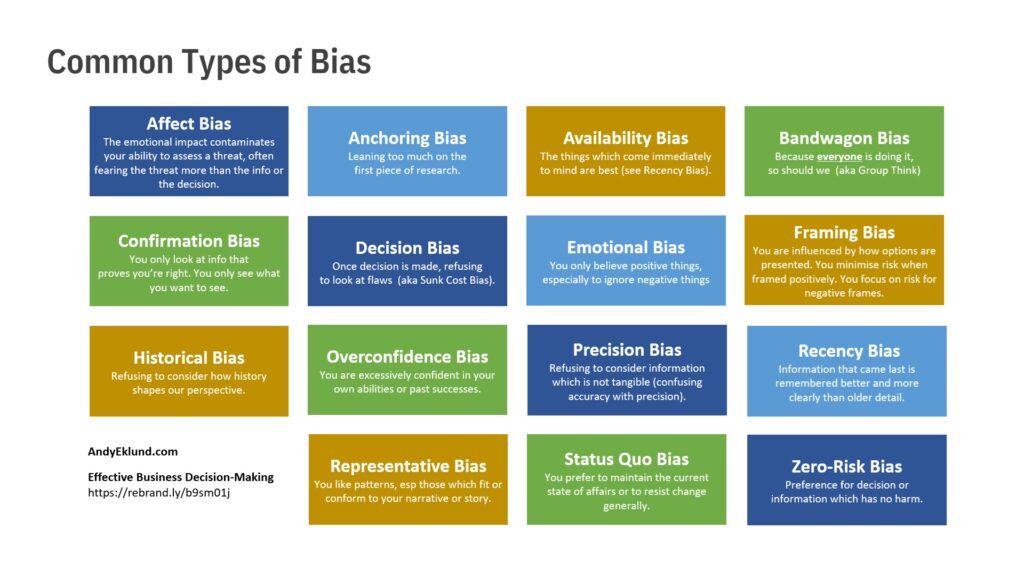

Also, be aware that information gathering also involves information bias: the tendency to search and use data that mis-informs your thought process, and ultimately your decision.

One important way to keep bias at arms-length is remembering never make a business decision without context. To understand context, you need to gather multiple pieces of information and compare and contrast them against each other. In other words, you don’t know if something is “good” until you compare it to something similar.

Gathering information means finding the most appropriate resources, which may be inside your organisation (such as experts or people who’ve addressed similar problems) or outside of your organisation (such as talking to industry veterans who can give you a world view).

Here’s something to consider. More often than not, inside information proves you right, and outside information proves you wrong.

Either way, effective decision-making in business demands you should do both. Gather information which both/either proves you right and wrong. (Welcome to ‘context.’) Welcome information from a variety of different sources. Gather both quantitative and qualitative research. Talk to people who understand or are impacted by the goal, decision or problem directly (design thinking).

Best of all, look for information which may inspire different solutions or alternatives … which leads to step 3.

Click here to download a PDF chart of graphic below of common bias and ways you might minimise bias in your decision making.

Step 3: Identify as many alternative solutions as possible.

You want volume, which is generally called “frequency” in creative philosophy.

One reason why you want as many different ideas as possible is because stakeholders have different needs or wants. Involve these stakeholders in the brainstorming, if possible. If the conversation is managed well, these stakeholders don’t brainstorm ideas they don’t want.

You should also take a moment before you begin brainstorming in earnest to define how you’re going to judge the ideas. What criteria are you going to use? (For example: cost, direct revenue, helps build a database of information.) Finally, do you supervisors or fellow decision-makers agree on these standards? If not, you’re playing two different board games.

Finally, generate your ideas first, then judge them. Don’t mix hatching and grading. (After you jump, scroll down to #3.)

Step 4: Evaluate all alternative options.

Once you have different options, now you should analyse them as a group. This is purest form of critical thinking. Critique the ideas against the decision that needs to be made. Will it address the problem? Critique the ideas against each other. What makes this idea better than that idea? Does it tell you something strategic about the better idea? Critique them against the criteria. Will one be better or more successful faster? Finally, can you critique the best qualities and merge them into a super-better idea?

If it’s helpful, and to speed-up decision-making, remove or minimise the worse ideas so your decision-making is from a small pool of the best alternatives.

Two of the most obvious tools for this step is a SWOT Analysis or a Decision-Tree Analysis or Matrix. If you don’t do this in the latter, you may also want to double-check your alternatives against the different stakeholders’ needs. Or, compare and contrast trade-offs. Rarely is one alternative cleanly above all other options. You almost always have to compromise something.

Step 5: Make your decision.

Make your decision by choosing the best idea offering the best balance of success and feasibility.

At this stage, you may want to re-inforce or reflect on the criteria you’ve used to choose the best ideas if your next step is to confirm your decision with team leader or supervisor.

Personally, at this point, I also like to have two or three back-up ideas to put in my back-pocket. (Not just my Plan B … but my Plan C and Plan D. I like options, especially if the first idea doesn’t work. When stressed, the first thing to fly out the window is your creativity.)

Step 6: Implement your decision.

Once you – or your senior leader – gives you the ‘all-clear,’ you now need to take the biggest step. You need to put your idea into action. (A good idea that isn’t implement is still a bad idea.) Whether it’s a simple plan with benchmarks and milestones vs a detailed project management time-line, map out your action steps to you can share with others, collaborate to improve if needed, assign roles and actions, and monitor its progress to determine if your decision was the right one.

Step 7: Review your decision and its impact overall, as well as reflect.

It’s important to remember the seven steps of effective business decision-making are actually a circle. Once you reach Step 7, it’s important to reflect back on Step 1. In other words, did your decision lead to success? How do you know? Did you have a benchmark of where you were to show how far you’ve gone? (SMART Goals are one way to do this.)

- What measurement tools are you using? Are these tools in alignment with what your stakeholders want to see as a clear success?

- Did any part of the decision have a negative impact? And, could this be addressed if you need to re-start or repeat the action plan?

- Where there any other unseen benefits or drawbacks to the decision, the solution or its implementation?

Perhaps most important, what did you learn about this process? What did you learn about yourself?

It’s an old cliché but a valuable one. Reflective leaders are effective leaders.

Also ...

It’s possible that your decision, idea or plan wasn’t 100% effective, and you may need to repeat or adjust the plan for a second round. This is another reason for reflection.

- What would you repeat as is a second time?

- What did not work at all? You want to avoid this the second go-around.

- What worked OK … but could have been better? This is the best part of your reflection. What can you do to improve the plan next time?

Any other advice or suggestions, or even adaptations to this seven-step process?

Please comment below.

In contrast to these seven steps of effective business-decision making, you might also compare this process with the …

Steps of Creative Thinking (scroll down to Step 2: Use a creative problem-solving process)

No comment yet, add your voice below!