Uncover a True Insight is Post #3 in a series from a presentation entitled 11 Great Creative Slip-Ups: The Most Common Mistakes in Brainstorming. The introduction to the series begins here.

The Problem: Using shallow research to make strategic decisions

Where does an idea come from? A flash of inspiration? A light bulb moment?

Yes, but here’s a better, more specific answer: from an insight.

Each and every time. No ifs, ands or buts.

And where does an insight come from? According to The Macquarie Dictionary, an insight is the ‘essential understanding of a given topic.’

An true insight is gained through obsessive absorption of knowledge about a particular topic until a person can figuratively step away from the information and say very simply what the data means.

Everything you need to know is in that sentence.

Ideas come from an insight. Insights come from knowledge. Knowledge comes from information. Information comes from data.

I call it the , but to a few lovely if obscure people, it’s also known as the DIKW Pyramid.

Here’s where an insight does not some from: shallow research. Barely scratching the surface of its understanding, shallow research is too flimsy to be directive, and not enough of the right data to be informative, much less to uncover any truthful insight.

There are lots of culprits. Not enough time to conduct research has to be one of the primary reasons. Research can also be expensive. And, because it’s a drain on resources, the Internet often fills in as a research device – which isn’t necessarily bad, unless it’s the only method that’s used.

(I once had a student who told me with a straight face: Well, I didn’t find anything on the first page of Google. !!)

Primary research – acquisition of data first-hand – is always preferred. Secondary research – an analysis and summary of other’s outside research – is an excellent substitute. However, let’s be honest. Both can be difficult to get when your back is up against the wall.

The Solution: Uncover a true insight

Here are some suggestions if you have limited time.

1. Deeply understand the problem.

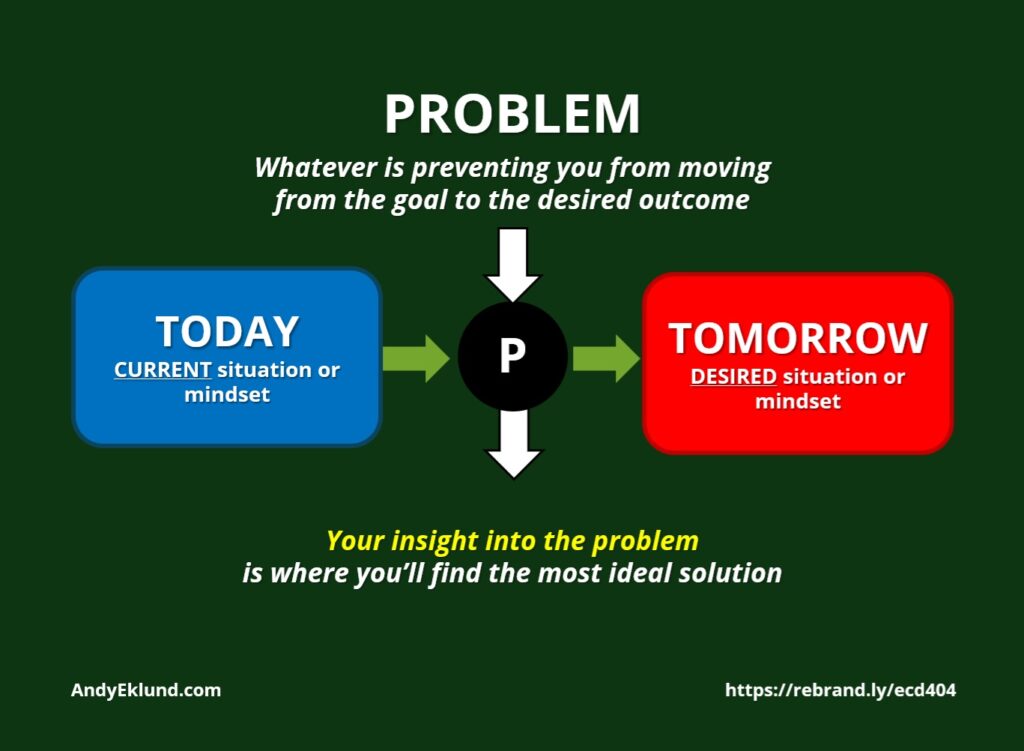

In The Concept of a Problem, Gene Agre says “a problem is the gap between the current state of affairs and the desired state of affairs.” The problem (pictured right) is what stands in the way of moving from today to the future. By analyzing the problem, you uncover insights which lead to ideas which might solve the problem.

It’s also important to know exactly what the problem is.

Engineer and inventor Buckminster Fuller once said: “A problem adequately stated is a problem well on its way to being solved.” If you know exactly what the problem is, you will know how to fix it.

It also suggests do not solve the wrong problem – but that’s another article for another day.

My creative team was once approached by a global (and Western) women’s cosmetic brand to launch a new line of hair coloring in China. The primary audience was women, aged 35+, who believed hair coloring was an outward sign of prosperity. We knew beauty salons would be an important engagement point.

While talking to women one afternoon, I had a customer look very concerned. She said she didn’t know if her husband would like the new color. The other women immediately joined in. We realized we’d uncovered a true insight that none of our team knew as a Western audience. A woman’s husband was an essential influence on her hair color choice. If we didn’t address the issue of the husband’s perspective, there would be a good chance we wouldn’t sell more hair colouring.

2. Focus more on psychographics, and less on demographics

It’s easy to find and understand demographics: they’re precise, concrete facts that would stand up in a court of law. But these type of chilly statistics – a person’s age, their salary, education or zip/postal code – do not lend themselves easily to brainstorming.

Psychographics are always preferable. They articulate and measure the inner thoughts of the end user, not just what a person believes but why their thoughts, attitudes and opinions are important to them. These elements are based on their values, all of which determined how they ultimately behave.

For more on this topic: .

Remember, you cannot change a person’s mind or behaviour unless you know what they think right now.

The behaviourial aspects are essential because they show how engagement might be translated into belief and action. The best ideas always spring from natural behavior, and psychographics indicate what those behaviors are or might be.

People often don’t know where to find psychographic information. Most organisations would go to two places: internally, in either the marketing or R&D departments, or if you have an external advertising or marketing agency.

Or, the fastest, most direct way …

3. Use less Internet and more real life

Master spy novelist John le Carré once said, accurately, “A desk is a very dangerous place from which to watch the world.”

Very few things help brainstorming as much as real life experience. That includes moving away from your desk and going out and talking face-to-face to the end users who have the problems. If you need a term, they’re generally called . On other words, you go to them.

Your end user is far more likely to fully understand the problem, why it’s a problem, and what they’d prefer in terms of a potential solution. It is catastrophically wrong of anyone to assume they knew the end user better than the end user themselves.

To put yourself in the proverbial shoes of the target audience significantly increases your understanding of the audience which, in turn, can’t help but allow you to better uncover a true insight or key point that will springboard into potential ideas.

Even better, work with your end user to brainstorm potential ideas. In my 40+ years working in creativity, I have never had one person brainstorm an idea they’d never use themselves. It’s practically fool-proof if you go into the situation with an open, flexible and creative mind.

This may sound simple, or worse, condescending. But if you don’t know the difference between Listening to Understand vs. Listening to Reply, you may find useful.

Any other ways you’ve used to uncover true insights to improve your creative brainstorming? Please add your thoughts and comments below.

If you want to return to the original article with links to the other ‘Slip-Ups’, click here.

No comment yet, add your voice below!