As a way to get the creative juices flowing, I often talk in brainstorms about focusing on the problem – whether it’s defining it, organising them into groups, or refaming them to get a new perspective. All of these methods focus on the words used to describe the problem. This brainstorm technique is (sort-of) the opposite of words. Instead, draw your problem.

Whatever you call it – doodling, cartooning, sketching, or even something less artistic like scribbling – drawing is an ideal way to understand a problem from a unique or different point-of-view.

It’s said that words can be limiting, particularly if you don’t feel like you have a large vocabulary. And, if pictures are worth a thousand words, doesn’t it make sense that brainstorming through drawing might be a fun way to generate new ideas in a brainstorm?

Drawing Is Something People Have Always Done

I don’t know if the earliest cave painters had a problem to solve, but there is something primal about drawing. Perhaps the better word is childlike. Babies begin to express themselves either fumbling with words or scribbling with crayons. Something left-over from those days comes out whenever I hand-out paper and markers in brainstorms. The room is suddenly a flurry of activity and the temperature of the room goes way up.

Drawing also taps into a different part of the brain: the one focused on visual aspects instead of the words themselves. In effect, it’s a way to light up more parts of the brain at the same time, which automatically increases the brain’s output and stimulates creative thinking.

If you’re not yet convinced, a final reason is that scribbling or doodling is a great psychological tool. It fascinates me to watch how people take notes in my workbooks using drawing or scribbles instead of writing notes. There’s also significant research that shows doodling is helpful in other ways, such as boosting one’s memory.

Here’s a recent article – 10 Benefits of Doodling for Creativity, Productivity and Focus – on Canva that you might enjoy.

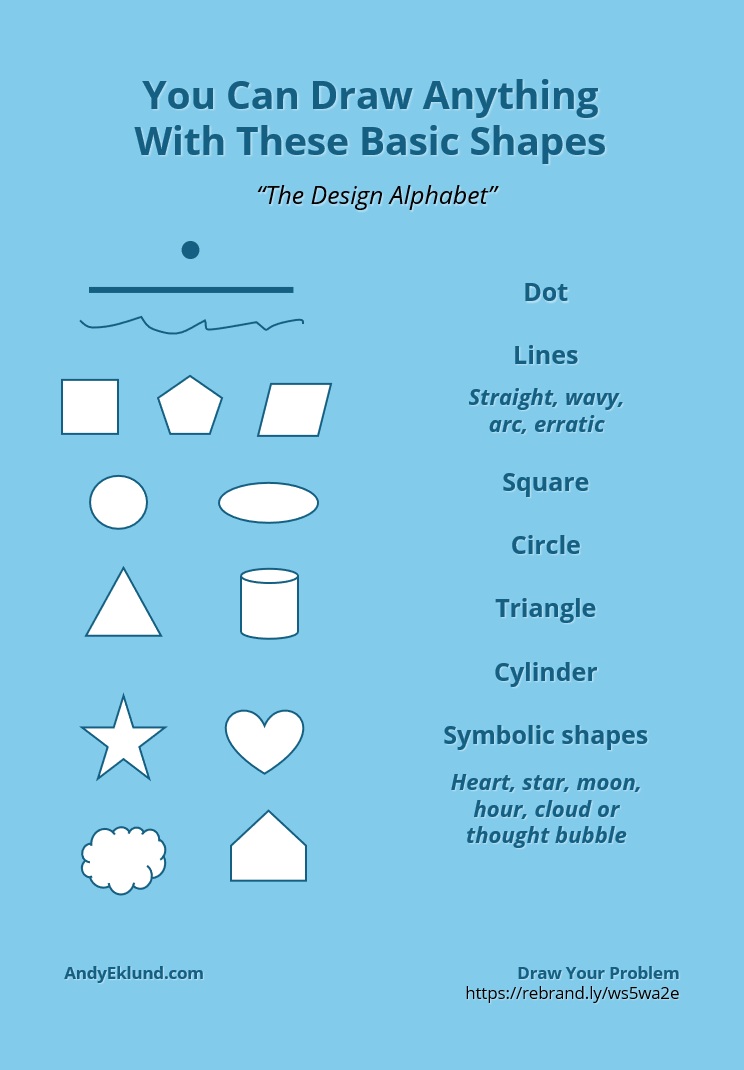

The Design Alphabet

Any skill requires its own vocabulary. Drawing is slightly different in that its vocabulary aren’t words, but shapes.

One of the first things I learnt in design school was what my professor Anna-Maria Hutchins called ‘The Design Alphabet.’ (Later on, I found the Design Alphabet was also a helpful tool of Design Thinking.)

Essentially, the ‘alphabet’ is group of the most basic geometric and organic shapes which comprise every drawing of any complex object. Each shape is simple and easy to draw, and by learning to draw them to articulate the problem or solution helps to increase one’s creativity and imagination.

Roughly in order, the shapes are:

- A dot

- A line – either straight, curvy (an arc), wavy or erratic

- A square, including its 2D/3D variations: rectangle, kite (deltoid), diamond (thombus), parallelogram, trapezoid, octagon or cube

- A circle, including its 2D/3D variations: oval, ellipse, sphere or hemisphere

- A triangle, including its 3D variations: cone, pyramid

- A cylinder

- Symbolic shapes – as opposed to the geomatric shapes above – such as a heart, star, half-moon, cloud or thought bubble, or house.

Always Start with a Review

When I’m conducting a working session on Design Thinking or LEGO Serious Play, or even for a brainstorm exercise, I start with a quick humourous review of the shapes.

Why review a circle? The operative word is: humorous.

I’m not teaching shapes, but using humor to make the participants more comfortable in the ‘artistic’ setting.

Also, as a workshop facilitator, it’s necessary for me to re-inforce the idea before the drawing begins that drawing/doodling isn’t about creating “art” at a Michaelangelo level of perfection. This flawless mindset always causes people to freeze up from fear. (It’s similar to asking senior people to draw with something as immature as crayons or coloured pencils!)

The point to make to participants is that everyone can draw well enough to express their issues, problems, concerns and ideas in a way that’s deliberately different than how we typically do it – through words.

When you finally get participants to get rid of the fear of embarrassment or rejection of their perceived lack of skill, it’s hilarious how everyone jumps in like they’re 5 years old again.

Instructions to Inspire People to Draw More

Materials

Use simple materials. No need for expensive art paper or tools. I buy my paper, markers, pens or pencils at a reject or second-hand shop. You don’t have to use coloured pens, although there’s research that shows colours are one additional way to light up more parts of the brain. You might also consider tracing paper, but read on for the reason why.

Standing vs. Sitting?

It’s a personal choice whether you want to sit down or stand up. When I stand up, I prefer larger paper, like flipchart paper posted on the wall.

Begin with the Problem

Start with describing the problem or situation that you’re in. Be simple and concise. If you’re doing this technique in a large group setting, you might go around the room and ask each person to phrase the problem in their own words, collecting their responses on a flipchart or whiteboard.

Start Drawing!

Seriously, just start. Don’t think. Don’t sit and look at a blank page. Doodle to get started. Stick figures are 100% fine as are figures with perspective and depth.

No judging. As Anna-Maria said in my very first art class: “If it’s a bluebird to you, it’ll be a bluebird to me.”

It’s important too to remember that “rawness” in a drawing is good. It allows other people to project their imaginations on to someone else’s work.

Encourage people to try several drawings, not just one. Even worse, don’t allow people to spend all of their time trying to turn their squiggle into something that’d hang in a museum. Again, the point is not artistic expressiveness. This isn’t a live drawing class. This is about using the visual aspects of your brain to draw the problem instead of using words. This last point is another reason why I ask people to use as few words on the drawing as possible.

Either walk around and encourage people to share, or deliberately mix people up to share and comment. Expect a lot of laughter and giggles, which is great. When people are more relaxed, their brain is less conservative and playful.

Encourage people to share, steal, adapt, change, start again, go back and draw more.

Remember too, as a facilitator, it might take some people more time to warm up. Keep encouraging but not overbearing.

Oftentimes people aren’t sure where to start. My best advice to them: start small. Start with one small aspect of what they’re trying to draw. If it’s a stick figure, draw all of them limbs before adding rich detail to the face. The moment people start drawing detail, everything slows down – and, they’re focused on the artistic quality rather than the imaginative potential.

Keep the Drawing Going!

If you need help to keep the attention and momentum going, try these suggestions.

Draw the problem from the point of view of someone else, such as the end user, a consumer, an expert, or a child. You might even try something non-human, like a dog, cat or bird. Or an emotion. Or a thing or event. The drawing does not need to be literal.

Speaking of birds, draw the problem from 30,000 feet. Or, from the floor up. Draw the problem from the side, or a few days later, or 10 years in the future, or 10 years prior. Try upside down, or looking inside out.

Make the problem a person. Add details to the person to reflect the problem. Or, draw several people who interact.

Draw the problem in context of something larger, like how it might fit in with a person’s day, career or work life, or family.

Make the drawing something like a cartoon – like you’d find in the newspaper – with panels or storyboards. You can continue to expand on this by adding supporting characters, or multiple story lines, or conflict and resolution. Pretend it’s a movie. How would you cast it? Score it? Where would you set the action?

Delete the irrelevant parts of the drawing. This is where tracing paper can be helpful, so you can trace the best elements of the drawing without destroying the original. Eliminating aspects of the drawing might isolate a kernel of truth or an interesting perspective.

Keep going until you have lots of images. Collect them together, or post them on the wall. Group them together in themes or concepts. Keep an extra page handy to write down ideas. I like to use post-it notes to write the ideas on top the drawings (again, so not to destroy the originals).

Look to see if there’s any patterns or repeating themes from the drawing. Group like-minded pictures together to help identify consistencies.

At some point, start to drill down to the purpose. What are we seeing that makes us look at the problem differently?

Before I finish …

Embrace your non-artistic self. This isn’t a brainstorm technique to win art prizes. Don’t worry if your drawing isn’t blue-ribbon quality.

If you’re the facilitator, protect people’s vulnerabilities and allow them to take risks. By letting people let go and have fun, you’ll find this brainstorm technique quite effective in generating new ways to solve the same old problems.

Any other tips or thoughts on how you’ve included drawing, doodling or sketching in your brainstorms?

No comment yet, add your voice below!