When two people communicate face-to-face, how much of the meaning is communicated through verbal communications versus non-verbal communications?

You may not recognise the name, but Albert Mehrabian authored one of the most famous studies in communications research delving into this specific question.

What’s more remarkable is that his landmark research is even more relevant today. Because whether we like it or not …

How We Communicate is Just as Important as What We Communicate

First published in 1971, Mehrabian’s research is almost a quaint idea today, considering that most organisational and personal communications now uses decidedly non-face-to-face methods such as new, social and digital media.

But even so, his conclusions are still important because they influence how and what we understand and believe.

Here’s how his theory works.

You are part of a typical live or online audience where you can see and hear the guest speakers. The MC introduces the next presenter whom you see sitting off to the side, or in their own online window, looking both nervous if not sweating as they mop their brow.

When the applause starts, this speaker gets up and moves uncomfortably toward the podium or arranges themselves erratically in front of the webcam. They take a bit longer than usual to get settled, perhaps tugging at their clothing or several attempts to clear their throat. After some fiddly adjustment of their notes, they emit a long painful sigh before finally looking at the audience through smudgy glasses, squinting toward the audience or webcam to say in a tight, fearful voice:

I’m very excited to be here today.

If you were the audience …

Would you believe what they said or how they acted?

Let’s say this overwhelmed person had a particularly important message to deliver to you. Would you be able to see past the less-than-professional parts and listen to what they were trying to tell you?

Or, let’s pretend it’s in reverse. What happens when the speaker is so glossy, so smitten with themselves and their flawless hair and wardrove but the words coming out of their mouth is meaningless drivel. How much would you see past the blinding visual aspects to listen to what they were saying?

Welcome to the power of non-verbal communications.

(Remember, if you didn’t know already, this research is not relevant when only listening to a person’s voice, such as a podcast or on the radio. No face or body is visible.)

Audience Perceptions Are Guilded by Three Aspects of Communications

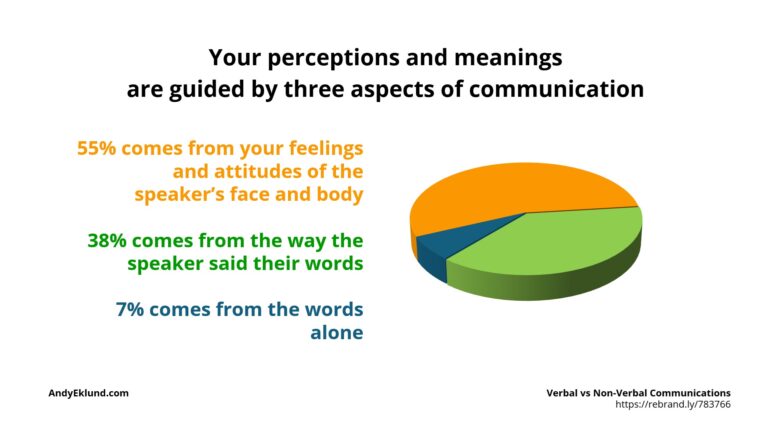

Mehrabian’s research found that audience’s perceptions – the combination of feelings, attitudes and understanding – are guided by three parts of face-to-face communications, sometimes called the 3 V’s.

Of the total communication …

- 55% of the message came from your perception of the speaker’s face and body (or Visual)

- 38% of the message came from the way the speaker said their words (or Voice)

- 7% of the message came from the words alone (or Verbal)

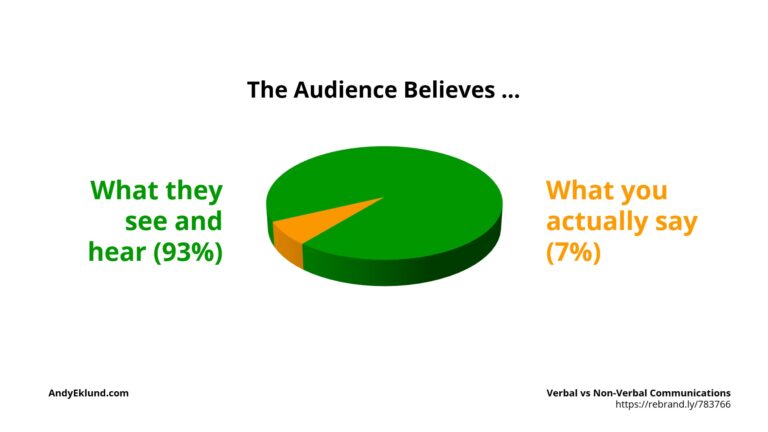

No surprise, his research suggests that the receiver (the audience) overwhelmingly trusts the non-verbal aspects of the speaker: 93% vs. 7%.

In other words, as an audience member, you trust what you see and hear more than you trust the actual words.

Here's What Verbal vs Non-Verbal Communications Means to You

From a speaker’s point-of-view, this means a couple of things.

There’s an important difference between writing your words and presenting your words.

They’re complementary – but very different – skills. Writing is editing everything you know about a topic down to information you put in a report or, increasingly, a slide – often using a Message House. Presenting is taking that information and distilling it to one message, with supporting facts or opinion. You aren’t ready to present until you can look at a slide, turn away and tell someone else the singular message of that slide, without hesitation and in one breath.

You cannot read your slides to the audience.

The audience reads your slides faster than you can aloud. You’re not only annoying (it’s hard to read when you’re saying the same thing), but it’s disrespectful. After saying the key message (which is essentially the title of the slide), you must talk about the slide: add your opinion, support it with a bit of detail, give us context understand why your message is important to remember. There’s also significant research now that shows conclusively that you do not help people remember your messages by reading them; in fact, you do the opposite. They’re far more likely to forget more quickly what you said when you read your slides.

You must know how you come across in a business situation.

Part of presentation skills training must involve being filmed giving a typical presentation in your typical style. To analyse it, you – and the trainer – should review it objectively, meaning you must pretend you do not know this person.

- Turn off the sound and watch the person. What do you think of the person? Are they believable? Why, or why not?

- Turn away from the screen and listen to the person. How’s the voice? Is it strong? Does it have variation? Is it too fast, or too soft?

- Listen only to the person’s words. Is what this person say make sense? Is there logic and flow?

- Ask for candid or anonymous comments. You might take the added step by having people provide you with their perceptions, so you can continue to learn (and improve) both your skills and your objectivity.

Isolate improvements in each area. Use these to rehearse on your own, returning in a day or two to be re-filmed so you can see where and how this person has improved.

Bring All Three Aspects Together Everytime You Speak

At the end of the day, if you are presenting at a critical meeting – either in a large auditorium, or from the head of a table at a small team meeting – you should give some thought to bringing all three elements of Mehabrian’s research together into one seamless and polished package. Otherwise, that recommendation, hypothesis or Big Idea, won’t be approved, and where will that leave you?

Any other thoughts on how you’d apply Mehrabian’s research on verbal vs non-verbal communications?

How else do you rehearse to ensure all three elements come together in one credible package? Please add your comments and thoughts below.

2 Comments

I am sorry about my lack of history knowledge but what is a “party line” ?

The telephony definition of a “party line” … a colleague who sits next to me (born in 1976) simply couldn’t understand how something like this was ever possible. Indeed.

“A local telephony loop, shared by as many as 16 different residences or business customers. Distinctive ringing comprising various combinations of short and long rings distinguishes whether a call was for you, or for another person on the shared line. There is no privacy on a party line, as any party can pick up the phone and answer the call or listen in on it. Placing outgoing calls was a free-for-all, as the caller must pick up the phone to determine if the line is available before placing the call. If someone else is using the line, the process must be repeated again and perhaps again and again in hopes that the line eventually will be available. Party lines are now rare in the United States, but not uncommon in rural areas in developing countries.”

A party line was also my undoing as a kid. My grandma used to be on our party line, and she frequently overheard me talking with friends about our plans on a Friday or Saturday nite … and of course who report me back to my parents.

Andy