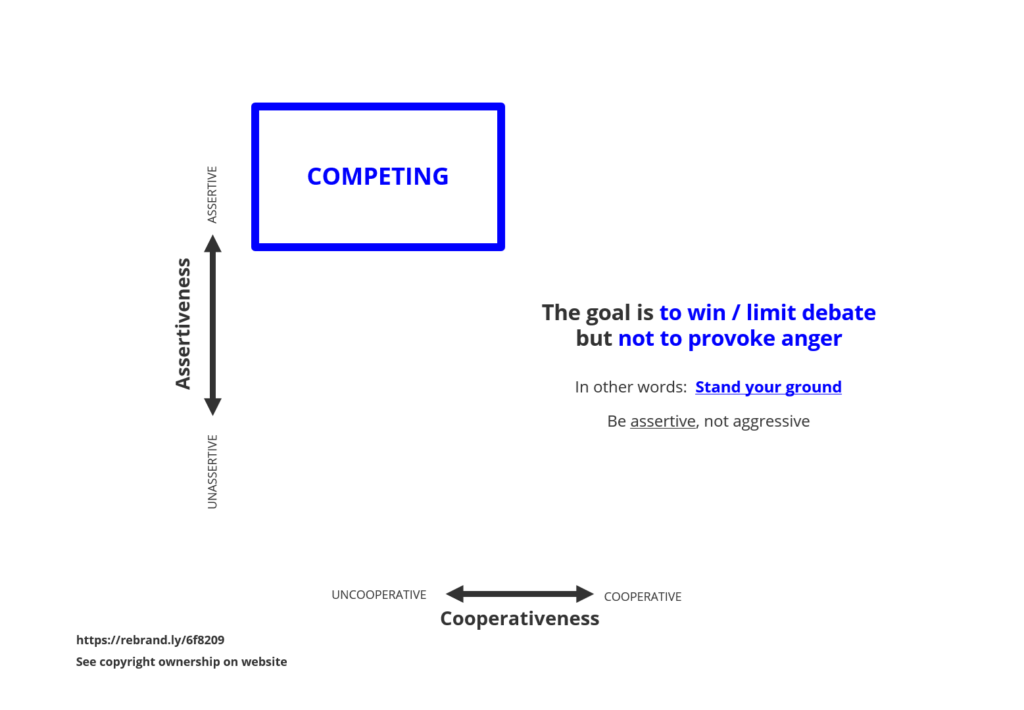

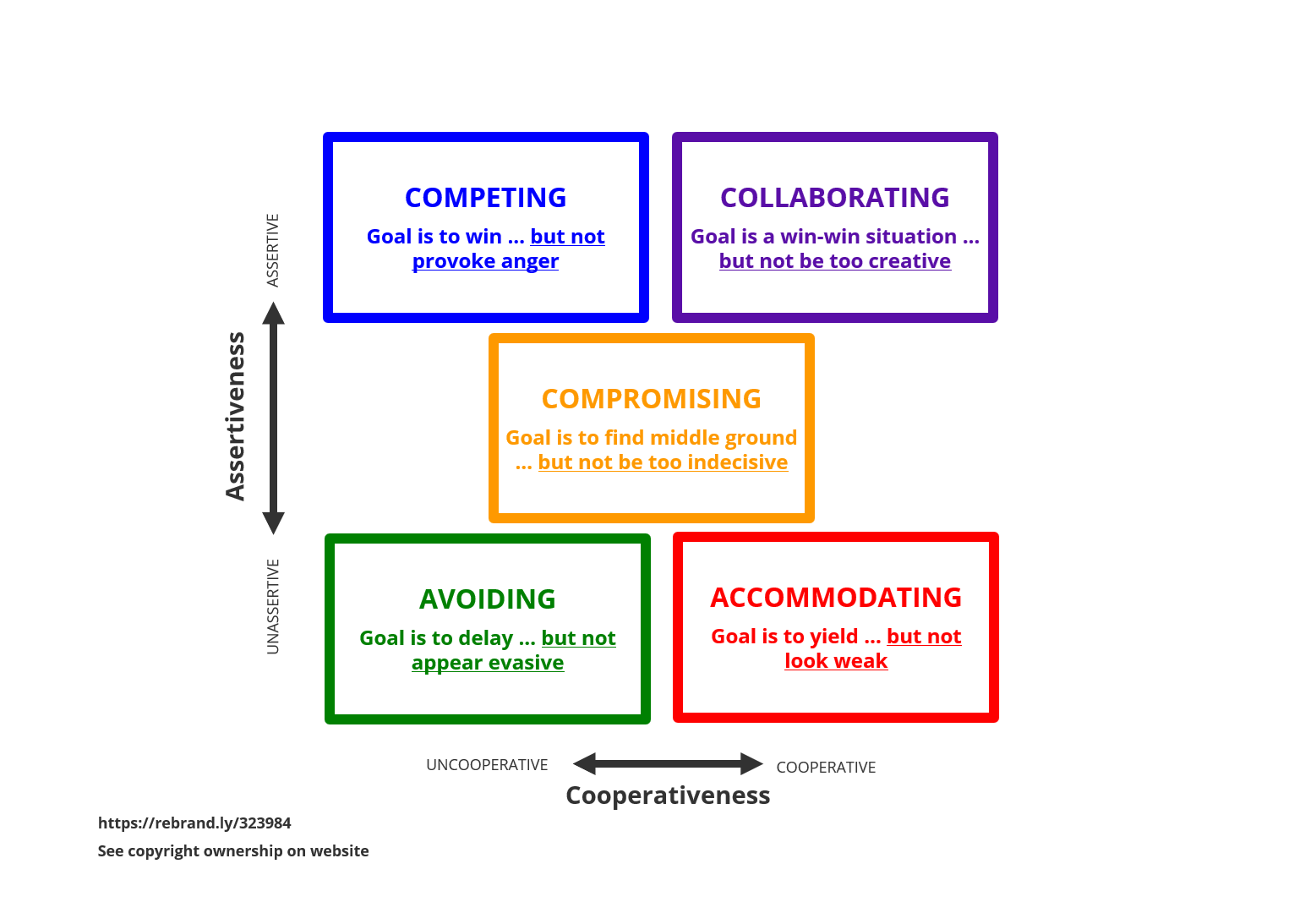

This article on Competing is one in a series of five about managing conflict and negotiation using the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument.

The introduction to the five-part series begins here. Links to the other four specific areas is at the bottom of this post.

Best when the Outcome is Vital, if not Necessary

Competing should be used primarily in situations when the outcome is vital or extremely important, particularly for any aspect that is not up for negotiation.

Here are some examples:

- A true bottom line

- A decision must be made ‘immediately’

- The outcome is mandatory: because of laws, regulations, compliance, or human safety (physically or emotionally)

- You must protect or defend your interests (some authority figures like to test if you have a backbone)

- A true moral outcome

If any of these are your situation – when some specific element will not be negotiated – your options are Competing or Collaborating.

Both require you to be Assertive, or you stand up for your own agenda and rights without criticising or humilitating the other party..

Collaborating is sometimes a better option because it’s win-win. (Both parties get what they need.) However, Collaborating takes far more time and resources. If your situation doesn’t allow for this, Competing at least ensures you meet or satisfy your concerns.

Go here for more on Collaborating.

Like all five modes, Competing has drawbacks. It can strain or damage the relationship with the other party which, in turn, provokes a variety of negative responses:

- Ongoing confrontation (especially with future negotiations, such as revenge)

- Lower motivation, interest, or initiative

- Not necessarily the best option as other alternatives are not explored

- Quite possibly the conflict reaches a stand-still or deadlock

If You Believe Competing is Your Best Option

Here are some questions to ask yourself which might minimise negative emotions or resistance.

How can you build your credibility?

To persuade the other party in a constructive way requires you to make your case, not just dictate. One way to persuade in the Competing mode is to explain why. Be transparent, clear and rational without appearing aloof. If any part of the decision reeks of a hidden agenda, your credibility is shot. That’s one asset you can’t afford to damage.

Can you prepare the other party for your decisions?

Conflicts between two parties are typically not instantaneous. Many times, an issue or concern has been simmering for a while. Doing some background work prior to the conflict discussion can uncover critical pieces of information. At the same time, it’s often beneficial to lay the groundwork for the conversation. Does something need to happen before this meeting? Can the other party be engaged beforehand to understand their perspective before a difficult decision needs to be made?

How can you transcend the conflict?

It’s easy during conflict to get lost in the nitty-gritty of the conversation itself and forget the real purpose or long-term objective. What are you ultimately trying to achieve? For example:

- What’s best for all of us, not just a few?

- We need to focus on the future, not just finding an answer which makes us happy today

By looking at the forest, not the necessarily the trees, it often helps to re-frame the problem for the other party. Perhaps more so, for you too.

How can you be specific?

In certain cases, it’s preferable to focus on the facts and not as much on the emotions involved. That’s as true for them as it is for you. (For example, don’t hold them responsible for your or your organisation’s problems.) As much as possible, try to ground your opinions in facts or with legitimate evidence. Make your intuition (your ‘gut reaction’) concrete. At the same time, if you need to manage emotions (yours, theirs), try to be specific. Frustration and annoyance are two different emotions.

How can you show respect?

This isn’t just an Asian concept to allow the other person to ‘save face.’ This is about being respectful and professional. At the end of the day, both parties are people first. That’s why the conflict should be dealt with as an objective topic, and that decisions should never be taken personally.

How can you show you’re listening?

This point can be divided into two parts: listening to rational points, and listening to emotional needs. First, do you have full perspective on the conflict? If you listen to the concerns of the other party, can you glean anything valuable to help improve the overall decision? Listening also creates “space” by bringing a breath of calm to both sides. Second, can allowing the other party to “vent” be therapeutic? You may learn something from their emotions. Also, never take away a person’s need to vent.

Finally, Competing should not be confused with totally dominating the conversation. Within reason, hear out the other side.

How can you demonstrate fairness?

In true Competing situations, the conversation is probably not equal. You are an authority figure. You may have to make or impose the final decision. Even so, a neutral facilitator (someone else, or even you wearing a different ‘hat’) might help bring credibility to the discussion. In certain cases, this may prevent side-conversations or tangents which may slow down action. Sometimes (if possible) it’s helpful to offer concessions, especially over things which are valuable to them but which cost you nothing. A common example? An apology.

How can you reward the other party rather than impose threats?

Fear is not a constructive motivator. Rewarding people – especially when the change process will be difficult – will position you as an engaging leader, one whom people will want to follow in the future. Be creative with the types of incentives you might offer. This might be a good topic to brainstorm with the other party, primarily to engage them in the decision and its after-math.

In this area of Competing, what are your experiences in managing conflict or negotiation? Please share your thoughts and stories in the Comments section below.

This article is my own interpretation of TKI. The artwork is my own.

All copyright is owned by Kenneth W. Thomas & Ralph H. Kilmann (1974), “Conflict Mode Instrument,” XICOM Incorporated, 33rd Printing, 1991.

As a reminder, the series about the TKI instrument begins here.

For each individual post, click on the following:

No comment yet, add your voice below!