Working in a professional services firm for much of my career, and then later as a teacher and instructor, I’ve learnt the power of good questions. But that begs – ironically – the thought: What makes a good question good?

While we’re at it, we might as well discuss what makes bad ones bad.

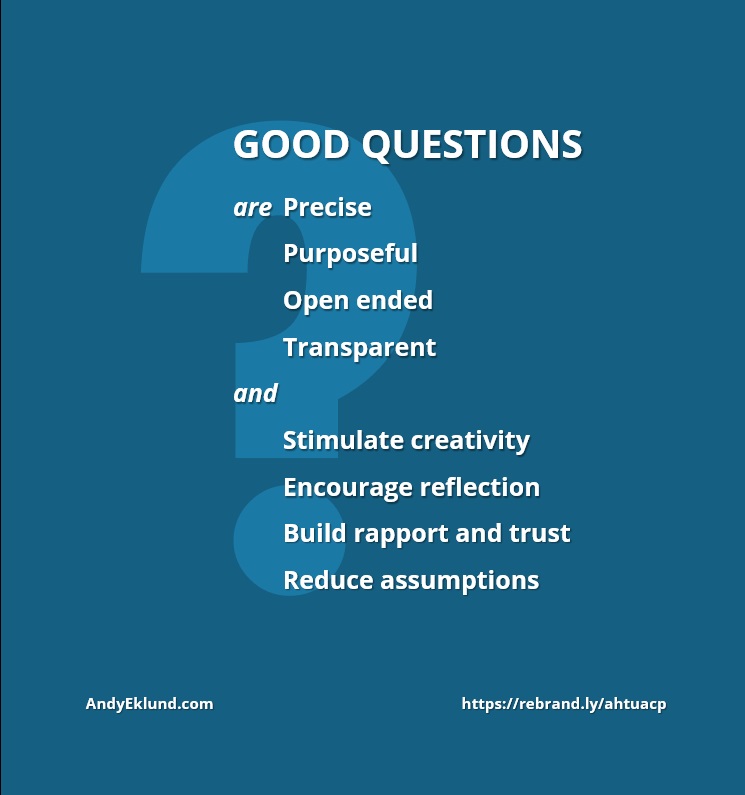

Good questions ...

Are precise. Their words are clear and specific to the respondent, not just to you.

Relate to a specific purpose, goal or intention.

Begin with low cognitive thinking (they ask the respondent to recall information) and lead to high cognitive thinking (they ask the respondent to evaluate or give an opinion about the information they’ve remembered.)

Often have more than one correct answer.

Encourage curiosity, to stimulate more thinking or research.

Encourage reflection after answering the question, so they retain what they know.

Build rapport, trust and asked in the spirit of transparency and honesty.

Reduce assumptions between parties to clarify and find common ground.

Also …

You can find examples of the two most basic types – closed and open – in a related article The Different Types of Questions.

Know too that bad Qs distort

According to Monash Business School in Victoria, bad questions are any question that distorts the fundamental communication between the questioner and the respondent.

In other words, bad Qs …

Confuse.

Intimidate.

Elicit an inappropriate answer, especially an unwanted or unwelcome emotion.

Are biased, often deliberately influencing the answer.

Are the ones where you (should) already know the answer.

To be more precise, here are the nine types of bad questions with examples.

1. Vague Qs

Vague questions don’t have a clear purpose or intention. What information are you trying to get? You don’t want the respondent to freeze up, spending more time thinking ‘What are they really asking me?’ and spend less time answering the question.

- Example: What did you think of today’s workshop?

- Improved: What are the top three things you enjoyed about today’s workshop?

2. Leading Qs

These type of questions have (a suggestion of) the answer built into the question. These types of questions can come across as arrogant.

- Example: How great is our new restaurant?

- Improved: How would you describe our new restaurant?

3. Loaded Qs

Loaded questions are loaded with bias. They assume the respondent feels the same way as the person asking the question. Remove your biases and let the respondent do the thinking.

- Example: Are you going to vote for that incompetent misogynist?

- Improved: Who are you going to vote for?

4. Double-Barreled Qs

It’s natural to want to ask two questions, especially if the second question is “why?” They need prioritisation. Experts suggest to not give a preface before asking both questions. (“Here’s a two-part question …”) The respondent may jump to the latter question and not answer the first. Instead, ask one question, then the other. You may be more likely to get clear answers to both when separately asked.

- Example: When did you decide to become a mother, and why?

- Improved: When did you decide to become a mother?

5. Double Negative Qs

Double negative questions have two negative words which make the opposite meaning true, likely confusing the respondent. Typically, make general questions positive.

- Example: Do you oppose not allowing us to have Friday’s drinks downstairs?

- Improved: Are you OK with allowing us to have Friday’s drinks downstairs?

6. Absolute Qs

Absolute questions use an absolute term, such as always, never, only, everyone, no one, etc. They add unnecessary judgement.

- Example: Don’t you think only Australians should apply?

- Improved: Do you think Australians should apply?

7. Unclear Qs

Anything with poorly chosen words – usually trendy slang, jargon, foreign words, or worst of all, in metaphors – confuse the respondent.

- Example: How has AI been a game-changing shift in your market?

- Improved: How would you describe how AI has changed how your organisation has gone to market?

8. Random Qs

Random questions are irrelevant and out of context.

- Example: In the middle of an interview, you ask: “Where do you get your fresh flowers?”

- Improved: If you must ask about the flowers, ask after the ‘interview’ is over.

9. Unanswerable Qs

These questions are so broad that there’s likely not an answer, or the answer is incredibly complex.

- Example: What is love?

- Improved: (Andy: I’ll let you decide your own improved question.)

Here too are more interesting thoughts in this area in the article The Surprising Power of Questions from the Harvard Business Review.

Any other thoughts? What are other good or bad examples of either? Please feel free to comment below.

No comment yet, add your voice below!