Louis Pondy’s Model of Organisational Conflict is the simplest and most effective formula to understand how to respond to conflict – at work or (despite Pondy’s focus on business) in a personal situation.

His 1967 article “Organisational Conflict: Concepts and Models” from Administrative Science Quarterly remains the Gold Standard for outlining the five stages of conflict in the workplace.

As leaders, managers or team members, it’s vital to understand this system given the pervasiveness of conflict at work, if not in life generally.

More so, by realising which phase or stage you or others may be evolving, it’s easier to respond to conflict in more appropriate ways to achieve a productive outcome for everyone.

Not to interrupt, but in a parallel track to this post, you might also check out the Seven Types of Conflict. To effectively recognize and manage conflict, you may need to know both:

- What conflict phase are you in?

- What type of conflict are you dealing with?

What is Conflict?

In the article noted above, Pondy doesn’t provide a specific definition of conflict … or at least one that’s quick to understand. Instead, I’ll turn to a contemporary colleague also working in conflict – Kenneth Thomas – for his simple definition.

Conflict is “an everyday condition in which people’s concerns – the things they care about – appear to be incompatible.”

There are key words in Thomas’ definition to consider.

- Everyday, which could be replaced with any of the following synonyms: daily, common, inevitable, normal, healthy, common, unavoidable.

- Condition, in that the situation, its history, the emotions, the relationships and back-and-forth behaviours are essential to understand to consider how to respond to conflict.

- Concerns, or “the things they care about,” are the crux of the conflict. The two best questions (one rational, one emotional) to start:

- What is important to you/them?

- Why is that – and not something else – important to you/them?

- Appear to incompatible, meaning that conflict often requires examination because the most suitable resolution may not be obvious at first to see.

Conflict is a Series of Episodes

In his research at the University of Pittsburgh, Pondy found that when the two (or more) different parties’ concerns were not understood, aligned or addressed, they moved – together or separately – through a sequence of five interlocking episodes or stages.

Ideally, he found each episode should begin with three basic thoughts to understand best how to respond to conflict:

- The considerations of a previous situation or episode,

- Parties often may not be aware of the earlier situations, and

- Each episode leaves an aftermath that affects the succeeding episodes.

To best manage and respond to conflict, Pondy believed it is critical to know and understand each episode in order to make the best decision about what to do next.

He also pointed out not every conflict passed through every stage.

- Some parties may never (want to) perceive they’re in conflict.

- Conflict can be resolved at any stage.

- An organisation’s success hinges on its ability to set up and operate appropriate systems to deal with conflict as they arise. These systems should be well-known and agreed-to by all appropriate people, such as department or team.

A Side Note about Kenneth Thomas

In 1974, Kenneth W. Thomas and Ralph H. Kilmann introduced their Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument, still one of the best known and most popular conflict style inventories. If you work with conflict but don’t know the instrument (popularly known as “TKI”) you should. I’ve written a series of posts on TKI. Or please check out Kilmann’s website.

What are the Five Stages of Conflict?

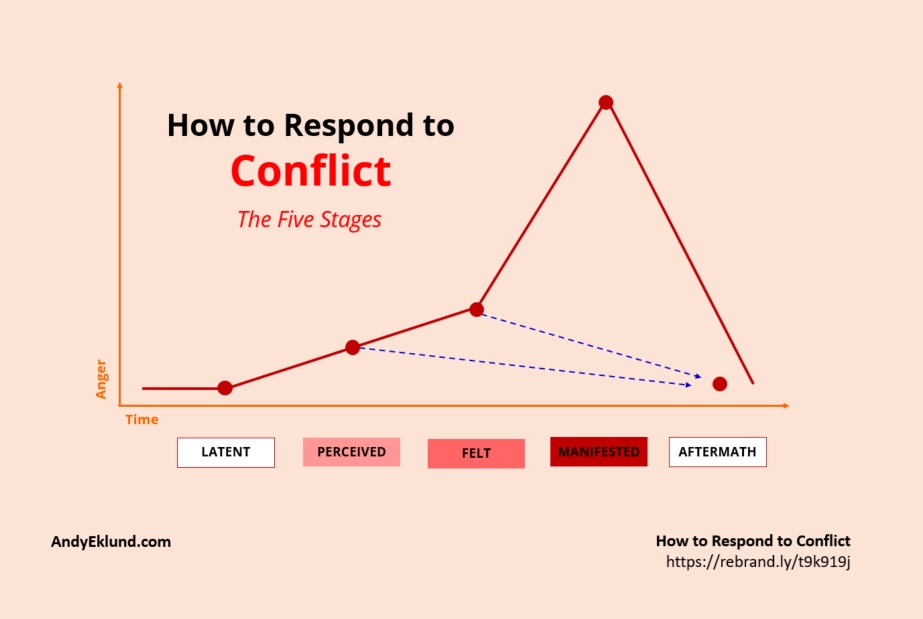

Here are the five stages or episodes to respond to conflict, including a general question helping to define the situation.

1. Latent Stage – or What pre-existing conditions are there?

2. Perceived Stage – or, What attitudes, moods or feelings are influencing the conflict?

3. Felt Stage – or, What perceptions do the parties have about the situation and each other?

4. Manifest – or, What ‘conflict’ behaviours are the parties using on each other?

5. Aftermath – or, How has the conflict been resolved, if at all?

Latent Stage

In the first stage, the conditions of the situation are ripe for conflict. But, as the title suggests, nothing observable is happening.

In other words, no one is actively engaged.

There may be many reasons for this, but the three most common are:

- One or more parties don’t realise there’s actually potential for conflict. They’re oblivious. Too busy. Focused on something else.

- One or more parties are deliberately keeping their heads down to avoid the conflict. They know something is potentially wrong but they choose to do nothing, hoping it blows over. Or it’s an act of avoidance (“that’s not my job”)

- One or more parties is waiting for something else to happen:

- a decision by someone else (a manager);

- the delivery of information, opinion or protocol; or

- perhaps worst of all, a ‘white knight’ to fix the problem for them.

We all know that conflict rarely just disappears. In fact, avoiding the conflict often makes it worse. (“Just rip off the Band-Aid!”)

Before I move on, there are a few additional considerations Pondy’s noted about the first episode. Even if one or more parties chooses not to do anything overt, it’s worth the thought to recognise and understand:

- The background or history of the organisation or the potential conflict

- The relationship between the parties

- The emotions and behaviours of all involved, and

- The expectations and assumptions the parties bring to the situation.

Perceived Stage

In the next stage, the episode has gone from no action to only one of the parties actively realising there’s a conflict situation. Yes, they may continue to downplay or deny the conflict, but they are conscious of the conflict.

As the episode transitions from the first to second stage, an initial problem may be the active party is frustrated with the other parties’ lack of action. For example, they may be …

- Annoyed the other party doesn’t realise there’s a problem

- Frustrated the other doesn’t understand the severity of the problem

- Insulted the other party is deliberately ignoring the situation

- Suspicious the other party is plotting against them

One thing the active party does not do? Consider the other party is merely oblivious there’s a legitimate conflict. In fact, there’s no alterior motive at all. Isn’t it easy for some people to add drama to a situation that doesn’t call for it?

To sum up the second episode, only one party is conscious of the conflict.

Felt Stage

In the third stage, the critical word is in the title. It’s not just that both parties are engaged, but they now feel the conflict.

The previous stages may be simply cognitive – aka rational thinking – where the conflict remains neutral. But with the addition of emotions, compounded by various aspects of the conflict (how it was realised, what someone said to someone else, personal reactions, team reations), the situation is now visceral, immediate, personal, and certainly more intense.

Stress, tension, anxiety and anger come to the forefront. As a result, there’s less cooperation, discussion and empathy among parties. The situation may not feel fair. Someone needs to be blamed. Feeling helpless is common.

In short, the situation is ‘on edge.’

Manifest Stage

I read a long-ago article interviewing Pondy. What I remember most was his suggestion this stage was in reality ‘open warfare.’

Not only are actions open, direct and visible, but the behaviours reflect the emotions: disagreements, arguments, confrontation if not immediate aggression. One party often tries to thwart the other’s goals. Some might try sabotage or backstabbing, while other go the opposite way – apathy, denial, ignoring, indifference, passive aggression – to prevent actions. While never appropriate in a professional setting, especially when they become physical, many behaviours are often things the participants might later deeply regret.

Given the situation or background, it’s often possible the parties may move directly from Perceived to Manifest.

Aftermath

The final stage of responding to conflict brings the arc to a close. The conclusion may range from one where the conflict is actively addressed and resolved, to one where the situation is worse than ever. Or, more often than not, there’s a smudgy middle ground when someone else – a senior leader, someone both parties respect (or not) – intervenes (asked or not) to guide or make a decision so direct and indirect parties can move forward.

Formally, the third party plays one of three roles:

- As a mediator, to help two parties to identify and make their own decisions.

- As an arbitrator, to hear and weigh evidence to make the decision on behalf of the two parties.

- As a litigator, where evidence is formally given to a judge to make a legally binding decision.

Positive Outcomes

When the outcome is ideal (regardless of how the parties got there), the conflict can become a springboard to better and stronger relationships. More honest discussions about working styles, situations or procedures. Higher satisfaction, cooperation and trust. Most of all, future conflicts are addressed more quickly and efficiently, if not dealt with in the Latent Stage.

Negative Outcomes

When the outcome is negative, it means the conflict was essentially suppressed and left unresolved, particularly if the two parties are left to their own devices. The relationship deteriorates if not completely dissolves, and worse, the negativity infects the team or even a more broad group of people like a department. There is little to no reflection, except at an intra-personal level. All future conflicts will be even worse.

Outcomes That Primarily Suit the Organisation

The middle-ground type usually involves someone at a higher level, like a manager, who informally intervenes. They may encourage true discussion where all parties can safely share their perspective and be respected. But, as Pondy said, it’s more common where one side feels they ‘win’ and one side feels they ‘lose.’ Apologies are made, but some may not feel they are genuine. Decisions are made, but some may not understand why. Or, worst of all, the decision doesn’t have anything to do with the individuals. The focus and benefit is on the organisation.

No surprise, companies who don’t take more active steps to encourage positive outcomes find team engagement plummets and employees, both good and bad, look for jobs elsewhere.

What are the Key Lessons to Respond to Conflict?

Many years ago, I attended a conflict resolution course because my supervisor at the time felt it necessary to raise the overall issue of conflict among the entire team before any potential issue might occur. The workshop facilitator helped our group – perhaps 20 of us altogether – determine the key lessons from Pondy’s research.

Those lessons were so important that I’ve kept that list ever since.

Prevention is best.

Always get ahead of the problem.

Time is not your friend.

Just because you may choose not to do something does not mean time has frozen everywhere else. A project could continue to go off the rails. Someone else may be continuing to make errors. Reputations could be destroyed. Do something, even if means going to talk to someone else who you trust or respect.

In conflict, neutral communications is essential.

Every conversation must be set in an atmosphere where issues can be raised and addressed without reprisal. And, every conversation requires two aspects:

- Conflict or not, all team members communicate their position specifically and constructively.

- Effective communications demands active listening. You had to be able to express another party’s position from their point of view, again both specifically and constructively.

Conflict can end at any stage.

As I mentioned before, Pondy never suggested parties must go through all five stages. In fact, everyone can choose to end the conflict at any stage. (That’s the point of the green arrows in the large chart above.) For example, one party can jump from the Latent Stage to Aftermath simply by bringing a potential problem to a team leader for them to action. As a team leader, make this crystal clear so others don’t make conflict worse by inaction, fear or poor communications.

Separate facts from emotion and assumptions, including your own.

Many aspects of conflict resolution revolve around the need for all parties to manage their emotional intelligence (‘EQ’). (For example, our conflict workshop was followed up by another solely on EQ.) Never make a decision based solely on emotions or assumptions. Learn to separate tangible, rational facts from false ‘truth,’ innuendo and gossip. Learn to recognize what you don’t know. Don’t make things unnecessarily personal.

Few people like someone else making decisions for them.

Be part of the process. Otherwise, you can’t get mad at someone else when you avoided responsibility in the first place. Sometimes, part of that responsibility is asking management to put appropriate environments, protocols and processes into place so people don’t have to guess or assumption when conflict emerges.

What other ways might you respond to conflict? Please add your thoughts and comments below.

No comment yet, add your voice below!