“Let’s ban PowerPoint in our meetings.”

What a common reaction, yes?

On one hand, it is understandable but clichéd.

On the other, it’s pointing the finger at the symptom, not the underlying problem.

So, what’s the problem with PowerPoint?

Before I go on, let me state that the problem isn’t just about PowerPoint. To be fair, the issues apply to Keynote, Google Slides, or any other slide-based presentation software such as Canva. They’re all great tools. I use them all. But like anything tool or product, you need to know how to use it to use it well.

So, what’s the problem with PowerPoint?

Part 1 of the problem: people are only taught how to make slides.

Part 2 of the problem: they aren’t taught how to communicate using slides.

Let’s be honest. Most people don’t know the basic principles of communications. Then we add on a poorly understood tool. No surprise, the whole thing becomes a mess.

But it’s all too common that executives decide the problem is the tool, not the presenter. This strikes me as blaming the clubs when the golfer can’t make a hole-in-one.

Banning slides is nonsense

A client recently decided PowerPoint was becoming so difficult that he gave his team – a sizeable group of 180+ people – the edict that:

- They were not allowed PowerPoint at all, or if they had to use slides …

- They were only allowed one slide for their entire recommendation.

First, removing a key aspect of presenting – slides, in this case – also removes something essential for the audience. Audiences expect to look at or read key points of the presentation while simultaneously listening to the presenter. If you remove everything – leaving only the presenter – you reduce the audience’s ability to adequately engage, understand and process information.

Second, limiting slides forces the presenter to resort to other methods to convey their points, usually ‘boards’– e.g., presentation boards, whiteboards and storyboards – which (ahem) are nothing more than PowerPoint slides without electricity. What does this accomplish exactly?

Third, I do not buy the argument removing slides will increase the effectiveness of the presenter. It actually does the opposite. It puts the entire weight of the presentation on their shoulders, and most people simply are not confident public speakers.

Did you know slides follow the basic science of communications?

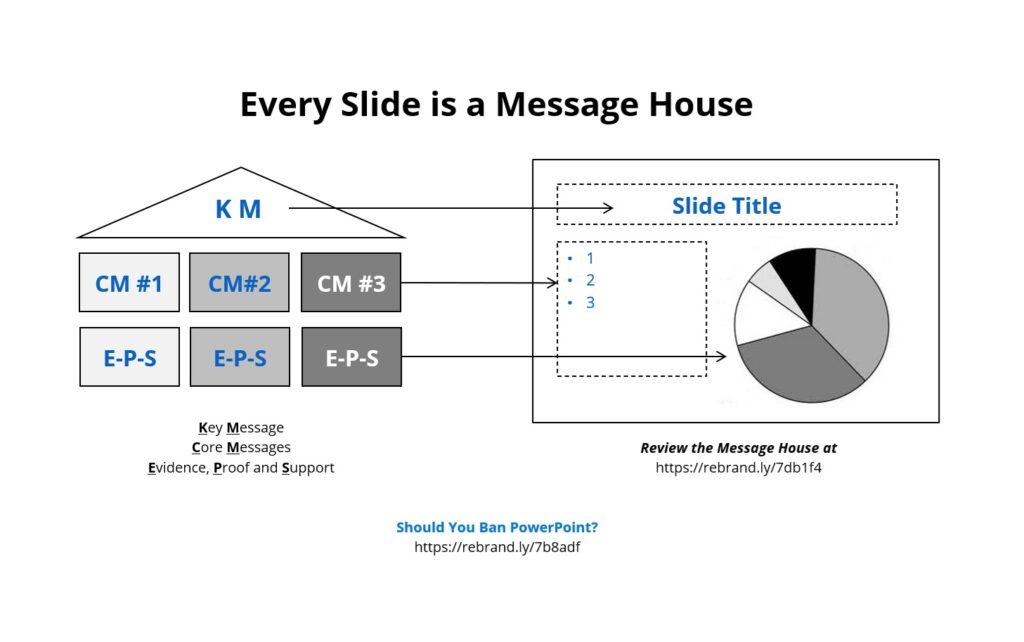

If you want to be a good presenter, but don’t know about the Message House, you need to. There’s a complete article on it here (the Rule of 3s).

In short, a presentation should be structured, organised and prioritised. (Notice three points.)

Every presentation has three parts:

- The beginning (the point of objective of your presentation as one overall “key or main message”).

- The middle (three “core messages” which support or substantiate your overall message), and

- The conclusion (the decision, the request for approval, the call to action, or a similar finishing statement to wrap-up and tie-back to your objective.)

Everything else – evidence, proof, and support – is organised inside this structure. Sometimes the three core messages (#2 above) are their own message house, allowing the structure to expand as necessary to meet the communications order.

Notice too that this three-level structure is the same structure of every slide.

- The slide title – which should always explicitly state the point of the slide itself

- Three bullet points (generally) which support the slide title

- An item or two (generally) of evidence (like a pie-chart or graph) to support the messages on the slide.

To not understand these core principles means the presenter is working against the science. To not organise what you want to say in a structured, discipline way is disrespectful to the audience.

Slides aren’t going away

PowerPoint and the like are here to stay. They’re simply this era’s variation of the slide carousels of yore. More so, rather than fight them, work with them.

Here are the basic elements you should consider as you build your slide-based presentation.

Start with an explicit purpose. Why are you talking?

To understand how to listen, the audience needs a clear understanding of why you are speaking. A typical member of the audience in a typical meeting will wait only 30 seconds to get a sense of why they should listen. If they don’t, they tune out. Instead, a sharp, crisp goal at the beginning makes you sound decisive, look confident, and demonstrate a total command of your subject.

Make complexity simple.

Think of the smartest person you’ve ever met. That person took complexity and made it simple for someone else to understand. That’s your job as a presenter.

Cut through the chaff and get to the inherent truth or insight, which in turn, leads or suggests a suitable recommendation or decisive plan of action.

Or, as my Nana Eklund used to tell me: Get to the point.

Be relevant to your audience.

You are the least important person in the conversation. Period.

Make your presentation about them, not about you. Make it relevant. Comprehend its impact to them. Change their opinion, attitude or behaviour. Speak to what you need the audience to do, based on what they know now about your topic.

The title is the most important part of the slide.

It tells the audience your point in a few words. Never use generic titled. (“Situation Analysis” is lazy.)

Remember too that every audience member will mentally leave the room. When they snap back into the room, they have no idea where the conversation is at. To get a sense of what you’re saying, they look to the slide title to re-orient them. Don’t give them a lazy slide title like “Situation Analysis.”

Most people nowadays think visually. That’s why slides can be overwhelmingly powerful.

Most people approach PowerPoint first with words and figures. Today’s communicators add one more element. They visually organise the words and figures in a way that makes them quickly understandable.

For every slide, you should always think where you want the audience’s eye to go first. What key point or message do you want to be conveyed first to the eye? Then, build around that centrepiece with sharply edited information.

In visual thinking, colour is not about prettiness. Colours should guide the eye to a specific part of the slide. The human eye prefers colour over black. The one colour you probably don’t see any longer is your organisation’s brand colours. Check your branding guidelines, and I’ll guarantee there is one “highlight” colour you should be using to attract your audience’s eye to a key section of the slide.

Never read your slide.

The audience can read almost 4-5 times faster than you can read. You reading the same thing they’re reading makes you annoying. Talk “around” or “about” your slide. That will give context to what the audience is reading.

Finally, the cover slide is the last slide you write.

Two points to close

The most intelligent perspective about PowerPoint came from Brian Hartzer, formerly in senior positions at ANZ and Westpac banks in Australia.

All effective business documents should be two things.

They are pro-active.

The author tells the audience what they are trying to do, and what they want the audience to do. They set a bar of expectation among the audience to listen, because they’ve explicitly said what the audience should listen for: a clear recommendation, a considered hypothesis, or an exact business decision.

They are concise.

The document gets to the point. They don’t ramble through irrelevant storytelling, glossy pictures or shallow presenters. They have an opinion, and the messages are sharp, positive and explicit.

Anything else to add to improve how PowerPoint is used effectively? Please add your thoughts and comments below.

No comment yet, add your voice below!